This year I wished I had a blog that functioned as an online readers’ salon. I read many books, and though most of them were neither new nor at the forefront of literary discussions in Canada, they each deserved a full review. I wanted to write about them because they were all in some way unusual, ambiguous, and thought-provoking.

Sadly, I didn’t have time to write when each book was still fresh in my mind. Instead, I hastily typed out some reactions and comments, and these formed the basis of what I wrote about the books below:

Hope Makes Love and Practical Jean by Trevor Cole

My Brilliant Friend and The Story of the Lost Child by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop by Amy Witting

Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs by Lina Wolff, translated by Frank Perry

Charlotte by David Foenkinos, translated by Sam Taylor

Summertime by John Coetzee

Of the six authors included above, three (Cole, Ferrante, and Coetzee) are currently well known and have earned multiple prizes and accolades. The other three, I suspect, might not be familiar to many Canadian readers.

What they have in common, and what intrigued me, is the strangeness of their characters. All of their main characters are damaged, isolated, crazy, or tragic in some way. Another common feature of these books is an unconventional structure or point(s) of view. They are highly sophisticated in their openness, their willingness to describe unconventional characters and relationships. This strangeness both comforted me, and at times puzzled me.

These books satisfied my curiosity about people. They are all classified as fiction, but at least some of the characters are based on real-life people. Whether “real” or not, each book gave me characters that satisfied my need to “meet” new people, to try to understand minds that are entirely different from my own. Part of the pleasure of reading is that it offers an escape, not only from the physical place and routines of one’s real life, but from the confines of one’s own mind.

At times my mind torments me with its anxieties, or I realize its smallness and its need to escape.

I like books that make me think—even about the writer’s purpose in producing them. I thought the books above captured the chaos and ambiguity of life more accurately than conventional narratives.

These novels were extraordinary and well written; yet I also saw flaws in them, and in some ways they left me unsatisfied. But perhaps this is a characteristic of writers who are not writing according to any kind of formula; they are not seeking, above all, to please their readers.

Part of my purpose in writing about these books is to ask questions about them. What gripped me? What puzzled me—in a good way, in the sense that I became an “active” reader who was wrestling with the questions and uncertainties they raised in my mind? What do other readers think?

What I’ve written below is taken from the hasty notes I made while I was reading (or shortly after finishing) each book. These notes are incomplete and fragmentary. They can’t be taken as book reviews. They simply give some insight (I hope) into one reader’s thought processes in attempting to interpret books and relate their ideas to personal experience. I have put the books in the order I read them.

My Brilliant Friend and The Story of the Lost Child

(by Elena Ferrante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein)

(by Elena Ferrante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein)

Note 1: These books are the first and fourth of the four “Neopolitan Novels.” Because of availability (and the quirkiness of the way I choose to read books), I skipped the second and third books in the series.

Note 2: The Neopolitan Novels have received rave reviews from all over the world. Elena Ferrante added to the mystery of her books by using a pseudonym and refusing to interact with the press. I heard that her true identity was “outed” in 2016, but I choose not to write about that here.

The 800 or so pages I read would be overwhelming to describe and critique in detail. The notes I made (see below) mainly express my dissatisfaction with the books. Yet I read these two volumes because I wanted to—I didn’t tire of them—they gripped me.

I’ve finished reading The Story of the Lost Child. I’ve been immersed in the book for weeks. Most of the time I enjoyed it, it intrigued me, but it left me unsatisfied. For a book that has received such huge accolades, it seemed flawed to me. For a while the mystery of Lila (the narrator’s “brilliant friend”) attracted me, but then I became frustrated because I couldn’t understand her at all. I felt as though the writer and the narrator, Lila’s friend Elena, were giving so many contradictory accounts of Lila that they didn’t know her either. Why would the “brilliant friend” not have gotten a higher education, moved away from the neighbourhood, and travelled? Was Lila paralyzed by her strange psychological affliction, the “blurring” of people? If she was mentally ill, I didn’t recognize her illness. What was it?

The way she had power over people was explicable when she was young; she was a beautiful woman, and obviously bright. But what explanation was there for the continued hold she had over people?

Why did Elena love Nico for so long? Nico reminded me of Paul [my ex-husband]. Yes, I loved Paul passionately for a long time, just as Elena did Nico. Yet he was not really the person I thought him to be. Like Paul, Nico was a womanizer, but he was apparently sincerely and utterly in love with each woman he was with. Well, there is my answer, I guess.

The book puzzled me because the many “characters of the neighbourhood” came into the story again and again, so they came to life—in a way. But I have a sense that something was missing—they never came to life fully; only Elena herself did.

Why did Lila disappear at the end? Did she commit suicide? Was there no other answer to explain the mystery of her?

I feel as though Ferrante (also named Elena) might be telling her own story, though calling it fiction.

Hope Meets Love and Practical Jean (by Trevor Cole)

Hope Meets Love was published in 2015 to rave reviews. Cole’s writing compels readers to love his characters, quirks, flaws and all. This page-turner alternates points of view between Zep, an ex-major league baseball player trying to win back his estranged wife’s love, and a neuroscientist named Hope who guides Zep through a scientific experiment designed to do just that.

Their voices are utterly different; Zep’s is at times profane, almost always funny, and casual in an endearing way. Hope narrates with the clinical tone of a scientist; yet Cole manages to put enough clues into what Hope writes that we can “read between the lines” to understand the human being behind the clinician. In fact, Hope is a deeply scarred person. The section of the book that reveals the source of her trauma leaves readers hanging on a razor’s edge of horrified suspense.

I had the good fortune to accidentally tune into a radio interview of Cole months after I finished reading Hope Meets Love. I was surprised to hear that he was worried about how he handled the subject of childhood sexual abuse; he was afraid that it made the book too “dark.” What surprised me was that Cole didn’t seem to realize that in creating the astonishing and beautiful love story between Hope and a young man who falls unshakeably in love with her, he had written a book that was overwhelmingly about the hope and power of love, its ability to outshine all darkness. Also, Cole’s writing is deeply funny because it makes obvious the striking contrast between Hope’s clinical analysis of love and her subjective experience of it.

I was so impressed with Hope Meets Love that I vowed to read everything else by Trevor Cole. I managed to pick up Practical Jean at my local library. This book about an outrageous murderer who believes she is killing her victims to spare them pain and suffering is meant to be a satire; I actually found it fairly plausible at first, until the murders became too grisly. It was an enjoyable read, though, filled with humour and the suspense of “Who’s next?”

Bret Eton Ellis and the Other Dogs (by Lina Wolff, translated by Frank Perry)

Bret Eton Ellis and the Other Dogs was a strange yet compelling book. It was convincing as a portrait of real people, though most of its characters were desperately sad. The book seems realistic because of its strange characters and apparent aimlessness—it’s more like “real life” than a standard novel would be. It certainly wasn’t uplifting, and I was trying to figure out why I enjoyed reading it nonetheless.

Maybe I liked it because its unusual structure and unpredictability kept leading me on. The book is roughly divided into three parts, each of which focuses on one major character; yet all three parts are united by the character of Alba Cambó, a fascinating woman who lives life to the hilt but knows she is dying of cancer. Each part of the book is a story-within-a-story, narrated by the main character from the first story, a young girl named Araceli. All of the three main characters are unbearably alone and sad, each in his or her own way.

Araceli never meets a man who matches Benicio Mercader, a man she fell in love with as a child. In her imagination, she created a romance between the two of them, and no real man could fulfill this fantasy.

Madame Elaine Moreau, Araceli’s French teacher, has no friends and hates her pupils. She is unable to connect with people properly. She even rebuffs a young boy who is in love with her—she is hostile to all warmth.

Rodrigo Auscias is a man who comes to Araceli, ostensibly for paid sex, but what he really wants is someone who will listen to his sad story of estrangement from his wife, Encarnatión. Even within their marriage, he is unable to achieve any intimacy with her, and she finally leaves him.

Madame Moreau is a mysterious character. She is totally unlikeable and blunt. She has a bleak outlook on life. Yet for some reason she is drawn to Alba. (There are suggestions that she worships Alba because she is a writer whose stories have been published in the magazine Semejanzas.) When she finds out that Alba is her student Araceli’s neighbour, she invites Araceli and Alba over for dinner at her flat.

The dinner is a failure; yet at the end of the book, we find out that Madame Moreau was Alba’s devoted caregiver during the last weeks of her life, after Alba’s lover, unable to cope with her illness, deserts her. It is Madame Moreau who takes care of all the funeral arrangements and the distribution of Alba’s possessions.

Rodrigo Auscias comes to Araceli as her first client for sex. (We find out later that Alba set up this meeting before she died; she wanted Araceli’s first john to be someone who would be gentle with her). But it turns out Rodrigo doesn’t want sex; he just wants someone who will listen to his story; for that he is willing to pay double, and he stays up all night to tell Araceli his story. This forms the last third of the book.

I became frustrated trying to understand this story. Rodrigo describes a marriage during which he spent many years being distant from his wife, watching her from afar in a worshipful way as she spent hours doing crossword puzzles. They hardly communicated. Why was Rodrigo initially so satisfied with this relationship?

As time passed, Encarnatión became a serious alcoholic, but Rodrigo still didn’t probe into the causes of her unhappiness.

As Rodrigo tells his story to Araceli, he keeps insisting that he has always loved his wife, but as a reader I can’t understand what he means by that. What unites him with his wife? Nothing, it seems, and it’s clear to readers that throughout the marriage she was always terribly depressed.

Then, Rodrigo relates, Encarnatión fell in love with Ilich, a man that Rodrigo has painted as a manipulative bastard. How can she love this man? What kind of man is Rodrigo, really, if Encarnatión prefers Ilich to him? Does Ilich have characteristics that make him loveable and attractive to women, that Rodrigo is incapable of seeing? Is the explanation simply that many women fall for men who are “bad boys”?

Wolff’s skill is her ability to make Rodrigo’s mysterious story enjoyable, somehow, and to make him a sympathetic character—at first. But the novel keeps unfolding to reveal the complexities of how all the characters’ lives are intertwined. Readers find out that Rodrigo is an unreliable narrator, especially when it comes to describing Ilich. It turns out that Rodrigo, Alba, and Ilich had a sexual threesome one night. This was part of a plan Alba had for getting Ilich out of her life. She knew Ilich would be able to blackmail Rodrigo with phone videos of the escapade. Ilich needed Rodrigo’s connections to get into the lucrative timber business.

At the end, Rodrigo is horribly callous to Alba. Near death, she tells Rodrigo that there is one thing that keeps her going—“The idea that I have done some good … that I’ve had some kind of positive impact on the people closest to me. If I have managed to make them feel happiness, my life won’t have been in vain…And I can die in peace.” (p. 289)

And Rodrigo narrates, “…I could hear my own voice saying that fuck no…she hadn’t been a positive force in my life. A curse is what she had been, an absolute curse and nothing else.” Rodrigo blames Alba for allowing Ilich to ruin his business and steal his wife. After this scene with Alba, readers suspect that Rodrigo has been a cruel man all along, ignoring his wife, being unfaithful, and generally being an idiot.

The great achievement of Bret Eton Ellis and the Other Dogs is that it seduces the reader into becoming engaged with characters who are almost unbearably estranged and sad.

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop (by Amy Witting)

This book by an Australian author I had never heard of was a lucky find at the library, presented as a new book though it was actually a reprint of a book published in 1989. Though it was the second book about Isobel (I For Isobel was published in 1990), it stood well on its own.

This was another book with strange characters. The main character, Isobel, discovers that she has tuberculosis and must go to a sanatorium. This is the setting for most of the book.

A sanatorium can be a microcosm for the larger world, and despite being in an institution, Isobel experiences close friendship and love. Particularly in the final section of the book, I found myself pondering what Isobel’s story suggests about the nature of love and its possible bonds.

When Isobel is finally healthy enough to leave the sanitorium, Dr. Stannard (whom she has a crush on) asks her if she would like to start a part-time administrative job working for him there, with the possibility that it would turn into a regular paid job once she is fully recovered.

Her initial reaction is to say yes, but she is criticized by Dr. Wang, who is a good friend of hers. Wang’s memorable advice is, “It is better to love those who give rather than those who take.”

But it’s the words of the “cold and contemptuous” Dr. Hook (whom no one likes) that rouse Isobel to change her mind. He says, “Why don’t you get out of here and grow up?”

He makes Isobel see that many of the patients who are cured have chosen to stay at the sanatorium in some capacity. And by doing so, they are voluntarily accepting a kind of permanent prison. They are doing it out of a refusal to grow up, a fear of striking out in the big world.

I realized how Isobel’s situation can apply to many people. There are many kinds of prisons that people choose to remain in. They can include a sterile marriage or a job that has become rote and doesn’t use one’s greatest abilities. Any refusal to change can be a kind of prison. Sometimes we have no choice (or no decent choice), and sometimes we accept imprisonment temporarily, if we have good reasons. But most of the time we dohave other choices; it’s habit and fear that make us remain in our prisons without bars.

Isobel ends up telling Dr. Stannard that she will be leaving. But she still finds his smile “enchanting.”

She thought, You may be a selfish, exploitative bastard, but in one corner of my mind, I’m going to love you all my life. (p. 311)

I had a flash of recognition when I read that line. I like the honesty of it, the wry admittance of our susceptibility to physical beauty and the way it can tug on our heartstrings.

Charlotte (by David Foenkinos, translated from the French by Sam Taylor)

One of the strangest things about this book is that it owes its creation to the self-admitted obsession Foenkinos has for Charlotte Salomon, an artist who died in Auschwitz during World War II at the age of 26. The book was written as an act of homage to her after Foenkinos discovered her art, which has been exhibited all over the world. He based his book on her unusual autobiographical project, published as Life? or Theatre?, which is a combination of writing, musical scores, and paintings.

Foenkinos calls Charlotte a novel or an “imagined biography.” Half a million copies of the book have been sold in France. This is impressive given the unconventional style of the book, which is written entirely in paragraphs consisting of one sentence or sentence fragment. This structure creates a stark, urgent tone. There is always a sense of compressed and repressed emotion. Foenkinos chose this style, perhaps, as the best way to convey the exceptional quality of Charlotte’s art and the depths from which it came: the rampant incidence of depression and suicide in her family, and the tragedy of the young artist who was forced to separate from the love of her life, then thoughtlessly betrayed—another victim of the evil of World War II.

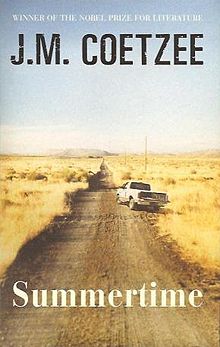

Summertime (by J.M. Coetzee)

Summertime is the third volume of a “fictionalized memoir” about a writer named John Coetzee by J.M. Coetzee. (I haven’t yet read the previous two volumes, Boyhood and Youth.)

It is an unusually structured book. Although the first short section is written from the “fictional” John Coetzee’s point of view, the remaining sections are narrated by women (and one male colleague) who were at some time close to John Coetzee, and are responding to an interviewer’s questions about their relationship with Coetzee.

The interviewer is seeking to understand Coetzee in order to write a detailed biography of a man who is now a successful writer.

The curious thing is that all of the women, despite being closer to Coetzee than anyone else, remark on his inability to be truly intimate with them. They all judge Coetzee as being incapable of sustaining an intimate relationship of any kind, whether a marriage, fatherhood, or any long-term relationship. All of the women express a strange dichotomy in their feelings about Coetzee; though they are attracted by something about the man, they all end up “giving up on him,” with varying degrees of anger, hurt, or frustration.

This book left me, the reader, with the question, “Is this how Coetzee, the real man, sees himself, or sees himself as reflected by the opinions of others?” What was his motivation for revealing himself in this way? Would I have understood Summertime better if I had read the previous two volumes? It makes me curious to find out more about the man, and to read more of his books.

Summertime is also a book about South Africa in the time of apartheid. The “fictional” Coetzee makes a point of doing rough labour on his own house instead of following convention and hiring black workers, which he could do very cheaply. I believe the author wants readers to think about how the Afrikaaners’ historical place in South Africa, their maintenance of apartheid, and their knowledge that this situation cannot endure affects an individual’s sense of belonging in South Africa. Also, how does it affect a person’s self-identity and ambitions? This sounds vague, but I would have to read more of Coetzee’s work to understand this, as I suspect it is one of the “real” Coetzee’s lifelong preoccupations.

The End … Not

The ramblings above show part of one reader’s book intake during 2016. I read many other books during this period, most of them excellent. For me, there can be no end to thinking about books and writing about them. In fact, I’ve just remembered two more books that fit in with the others in this post because of their rich and unusual characterization: A Curious Kindness, by Miriam Toews, and A Natural Curiosity, by Margaret Drabble. But this post is far too long already.

The journey of reading is an endless one. Part of it can be guided by recommendations one hears or reads. But I love the way the stops along the journey can be random and surprising. A book is discovered by accident at a library or a bookstore while searching for another book or another author. Something mentioned in one book leads to another book. And there is the magical way that a character, event, or philosophy in a book can speak to me personally to address something about my own life that is troubling me at the moment.